Korean Logic 101: Master Deductive vs. Inductive Reasoning

Hello! Welcome to Daily Han-geul, the place to upgrade your Korean skills to the next level!

Today, we’re diving deep into a topic that will truly elevate your command of Korean: the difference between deductive and inductive reasoning. This isn’t just for philosophy class! Understanding these concepts will empower you to participate in sophisticated debates, critically analyze news articles, and express your own arguments with precision and clarity.

These days in Korea, especially in academic and professional settings, the ability to construct a logical and coherent argument is highly valued. By mastering the language of logic, you’ll not only understand complex discussions but also contribute to them like a native speaker. Let’s get started!

Core Expressions

Here are the key terms you need to know to navigate the world of Korean logic.

1. 연역 (演繹) / 연역적 (演繹的)

- Pronunciation [Romanization]: yeon-yeok / yeon-yeok-jjeok

- English Meaning: Deduction / Deductive

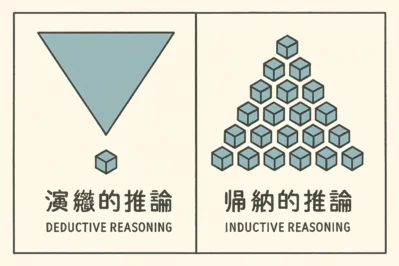

- Detailed Explanation: This refers to “top-down” logic, where you start with a general principle or rule (a premise) and move to a specific, certain conclusion. If the initial premises are true, the conclusion must be true. The Hanja characters 演 (yeon – to perform, unfold) and 繹 (yeok – to unravel) beautifully capture this idea of unraveling a conclusion from established facts. You’ll see this in formal logic, mathematics, and philosophical arguments.

-

💡 Pronunciation Tip:

When ‘연역’ (yeon-yeok) is followed by ‘적’ (jeok), the final ‘ㄱ’ (k) sound of ‘연역’ tenses up. This is a sound change rule called 경음화 (gyeong-eum-hwa), or “tensing.” So, instead ofyeon-yeok-jeok, the natural pronunciation is [여녁쩍 / yeon-yeok-jjeok], with a strong ‘jj’ sound. It makes the flow much smoother!

2. 귀납 (歸納) / 귀납적 (歸納的)

- Pronunciation [Romanization]: gwi-nap / gwi-nap-jjeok

- English Meaning: Induction / Inductive

-

Detailed Explanation: This is “bottom-up” logic. You start with specific observations or evidence and use them to form a broader, general conclusion or theory. This conclusion is probable, but not guaranteed to be 100% true. The sciences, from physics to sociology, heavily rely on inductive reasoning—gathering data to form hypotheses. The Hanja 歸 (gwi – to return) and 納 (nap – to gather) suggest gathering evidence to “return” to a general principle.

-

💡 Pronunciation Tip:

Similar to our first example, the ‘ㅈ’ (j) in ‘귀납적’ (gwi-nap-jeok) also undergoes tensing. It is pronounced [귀납쩍 / gwi-nap-jjeok]. This tensing of consonants following a final consonant (받침) is a very common rule in Korean.

3. 대전제 (大前提) & 소전제 (小前提)

- Pronunciation [Romanization]: dae-jeon-je / so-jeon-je

- English Meaning: Major premise & Minor premise

-

Detailed Explanation: These are the building blocks of a classic deductive argument, known as a syllogism. The 대전제 is the broad, general statement (e.g., “All humans are mortal”). The 소전제 is the more specific statement that connects to the major premise (e.g., “Socrates is a human”). From these two, you deduce a conclusion. The Hanja is straightforward: 大 (dae – big), 小 (so – small), and 前提 (jeon-je – premise).

-

💡 Pronunciation Tip:

These words are pronounced exactly as they are written, with clear, distinct syllables. This is often the case for formal, Hanja-based academic terms.

4. 성급한 일반화의 오류 (性急한 一般化의 誤謬)

- Pronunciation [Romanization]: seong-geu-pan il-ban-hwa-ui o-ryu

- English Meaning: Hasty generalization fallacy

-

Detailed Explanation: This is a very common logical fallacy, directly related to weak inductive reasoning. It occurs when you jump to a broad conclusion based on insufficient or biased evidence. For example, if you visit Seoul for one day, see two people being rude, and conclude, “All people in Seoul are rude,” you’ve committed this fallacy. 성급하다 means ‘hasty’, 일반화 means ‘generalization’, and 오류 means ‘error/fallacy’.

-

💡 Pronunciation Tip:

Notice in 성급한 (seong-geu-pan), the final ‘ㅂ’ (b/p) consonant from ‘급’ links to the next syllable, which starts with a vowel. This is called 연음 (yeoneum), or liaison. Instead of a hard stop likeseong-geup / han, the ‘ㅂ’ sound flows over, creating the smooth pronunciation [성그판 / seong-geu-pan].

Example Dialogue

Let’s see how two university students might use these terms while discussing a class paper.

A: 이 논리학 과제 너무 어렵다. 특히 연역 논증이랑 귀납 논증의 차이가 아직도 헷갈려.

(i nollihak gwaje neomu eoryeopda. teuki yeon-yeok nonjeung-irang gwi-nap nonjeung-ui chaiga ajikdo hetgallyeo.)

This logic assignment is so difficult. I’m still confused about the difference between deductive and inductive arguments.

B: 아, 그건 이렇게 생각하면 쉬워. 연역은 대전제에서 결론을 이끌어내는 거야. 예를 들면, “모든 사람은 죽는다”는 대전제와 “소크라테스는 사람이다”라는 소전제가 있으면, “소크라테스는 죽는다”는 결론이 반드시 나오잖아.

(a, geugeon ireoke saenggakamyeon swiwo. yeon-yeog-eun daejeonje-eseo gyeolloneul ikkeureonaeneun geoya. yedeul deulmyeon, “modeun sarameun jukneunda”-neun daejeonje-wa “sokrateseuneun saramida”-raneun sojeonje-ga isseumyeon, “sokrateseuneun jukneunda”-neun gyeolloni bandeusi naojana.)

Ah, it’s easier if you think of it this way. Deduction is drawing a conclusion from a major premise. For example, if you have the major premise “All people are mortal” and the minor premise “Socrates is a person,” the conclusion “Socrates is mortal” necessarily follows.

A: 그렇구나! 그럼 귀납은?

(geureokuna! geureom gwi-nab-eun?)

I see! Then what about induction?

B: 귀납은 여러 관찰을 통해 일반적인 결론을 내는 거지. “내가 본 모든 까마귀는 검은색이었으니, 세상의 모든 까마귀는 검은색일 것이다.” 처럼. 근데 이건 관찰이 부족하면 “성급한 일반화의 오류“가 될 수 있어.

(gwi-nab-eun yeoreo gwanchareul tonghae ilbanjeogin gyeolloneul naeneun geoji. “naega bon modeun kkamagwineun geomeunsaegieosseuni, sesangui modeun kkamagwineun geomeunsaegil geosida.” cheoreom. geunde igeon gwanchari bujokamyeon “seong-geupan ilbanhwa-ui o-ryu“-ga doel su isseo.)

Induction is reaching a general conclusion through multiple observations. Like, “Every crow I have seen was black, therefore all crows in the world are probably black.” But if you don’t have enough observations, this can become a “hasty generalization fallacy.”

Culture & Trend Deep Dive

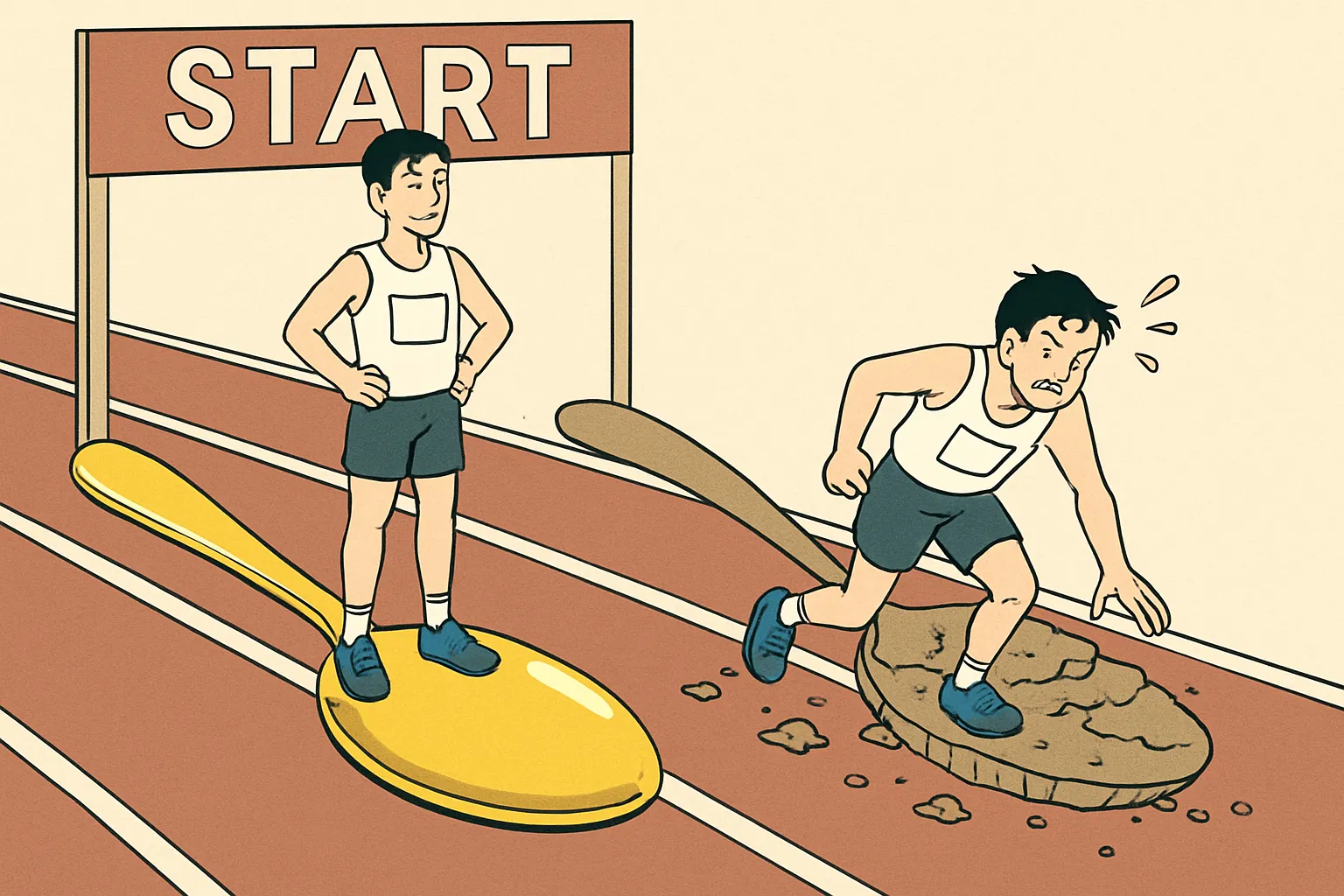

In Korea, logical reasoning isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s a critical skill tested in the infamous university entrance exam, the 수능 (Suneung), particularly in the language arts section.

You will frequently encounter the terms 연역적 and 귀납적 in high-level contexts like TV news debates (시사 토론 프로그램), newspaper editorials, and business presentations. Being able to identify whether a politician is using sound deductive logic or making a weak inductive claim based on limited data will completely change how you consume Korean media.

Furthermore, knowing how to spot a 성급한 일반화의 오류 is your secret weapon for navigating Korean online forums and comment sections. When a debate gets heated, pointing out a logical fallacy with the correct terminology is a sophisticated and powerful way to strengthen your position and show your high-level command of the language. It proves you can think critically in Korean.

Wrap-up & Practice Quiz

To summarize, deduction (연역) moves from general to specific, offering certainty. Induction (귀납) moves from specific to general, offering probability.

Let’s test your understanding!

- Fill-in-the-blank: An argument based on scientific data collected from 1,000 experiments to propose a new theory is a classic example of a ______________ (연역적 / 귀납적) argument.

-

Short Answer: Your friend tries one dish at a new restaurant, dislikes it, and declares, “이 식당은 모든 음식이 맛없어!” (This restaurant’s food is all terrible!). What logical fallacy is your friend committing? (Answer in Korean!)

Great job today! Mastering these concepts is a huge step toward fluency. Try creating your own sentence using one of today’s terms and share it in the comments below