Sentenced to Freedom? Unpacking an Existential Paradox in Korean

Hello! Welcome back to [Maeil Hangul], where we upgrade your Korean skills!

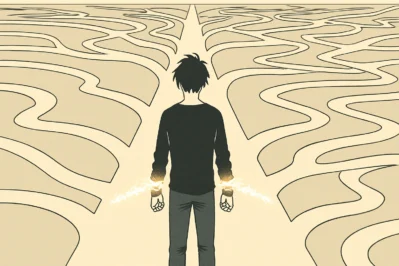

Today, we’re diving deep. Forget simple greetings and food orders; we’re tackling a profound philosophical concept that resonates deeply within modern Korean society: the idea that “we are condemned to be free.” This might sound heavy, but understanding it will unlock a new level of insight into Korean dramas, films, literature, and even everyday conversations about life and career.

Recently in Korea, there’s been a lot of discussion about the immense pressure on young people to make the “right” choices in a world of infinite options. This feeling of being burdened by freedom is a very real, contemporary issue. So, let’s explore the Korean vocabulary that captures this complex human condition!

Core Expressions for the Existentialist

Here are some key terms to help you navigate conversations about freedom, choice, and responsibility.

1. 우리는 자유를 선고받았다 (Urineun jayureul seon-go-bat-at-da)

- Pronunciation [Romanization]: [U-ri-neun ja-yu-reul seon-go-bat-at-da]

- English Meaning: “We are condemned/sentenced to be free.”

- Detailed Explanation: This is the core phrase from French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. The key word here is 선고받다 (seon-go-bat-da), which means “to be sentenced.” It’s a legal term with a heavy, negative connotation, usually used for criminals receiving a prison sentence. The power of the phrase lies in this paradox: pairing a negative verb like “sentenced” with a positive concept like “freedom” (자유). It perfectly captures the existential idea that freedom isn’t a gift, but an inescapable burden. We didn’t choose to be free, but we are, and we must bear the total responsibility for our choices.

2. 실존은 본질에 앞선다 (Siljon-eun bonjil-e apseonda)

- Pronunciation [Romanization]: [Sil-jon-eun bon-jil-e ap-seo-n-da]

- English Meaning: “Existence precedes essence.”

- Detailed Explanation: This is the foundational principle of existentialism. Let’s break it down: 실존 (siljon) means “existence,” and 본질 (bonjil) means “essence” (one’s fundamental nature or purpose). The grammar -에 앞선다 (-e apseonda) means “to precede” or “to come before.” The phrase means that humans are born into the world without a predetermined purpose. We simply exist first. It is through our choices and actions—our freedom—that we create our own essence and define who we are.

3. 기투 (Gitu)

- Pronunciation [Romanization]: [Gi-tu]

- English Meaning: Projection; a “thrown” existence.

- Detailed Explanation: This is a more advanced philosophical term, the Korean translation for Heidegger’s concept of “Geworfenheit” (thrown-ness) and Sartre’s “project.” It describes the human condition of being involuntarily “thrown” (던져진) into the world, into a specific time and place, without our consent. From this starting point, we must then “project” (기투하다) ourselves toward a future that we create through our choices. It encapsulates both the randomness of our birth and the active role we must take in our lives.

Example Dialogue

Here’s how these concepts might appear in a conversation between two colleagues discussing career pressures.

- A (후배 Hubae): 선배, 요즘 제 미래에 대해 생각하면 너무 불안해요. 선택지는 너무 많은데, 어떤 길로 가야 제 인생의 ‘본질’을 찾을 수 있을지 모르겠어요.

(Sunbae, I feel so anxious thinking about my future these days. There are so many options, but I don’t know which path to take to find my life’s ‘essence’.) -

B (선배 Sunbae): 그게 바로 ‘실존은 본질에 앞선다’는 말의 의미겠지. 정해진 답은 없어. 우리는 이 세상에 그냥 ‘기투’된 존재일 뿐이니까.

(I guess that’s the meaning of ‘existence precedes essence.’ There’s no set answer. We are simply beings who have been ‘thrown’ into this world.) -

A (후배 Hubae): 가끔은 그 자유가 너무 무겁게 느껴져요. 마치 ‘우리는 자유를 선고받았다’는 말처럼요. 모든 선택의 책임을 제가 져야 하잖아요.

(Sometimes that freedom feels too heavy. It’s just like the saying, ‘we are condemned to be free.’ I have to take responsibility for every single choice.) -

B (선배 Sunbae): 맞아. 하지만 그게 인간의 조건이야. 중요한 건 회피하지 않고 너의 선택에 책임을 지며 살아가는 태도지. 그게 진정한 의미의 참여, 즉 ‘앙가주망(engagement)’ 아닐까?

(That’s right. But that’s the human condition. What’s important is the attitude of living responsibly with your choices without avoiding them. Isn’t that what true ‘engagement’ (앙가주망) is all about?)

Cultural Tip & Trend Analysis

Existentialism in Korean Media

These philosophical ideas aren’t just for academics in Korea; they are powerfully woven into the fabric of modern Korean storytelling.

- The “Spoon Class Theory” (수저계급론): The popular concept of being born with a “gold spoon” (금수저) or “dirt spoon” (흙수저) is a perfect example of 기투 (gitu). It reflects the idea that people are “thrown” into vastly different socioeconomic circumstances which profoundly impact their choices and freedom.

- Films like Parasite (기생충): Bong Joon-ho’s masterpiece is a brilliant exploration of this theme. The Kim family is “thrown” into a basement apartment