Hello! It’s your favorite Korean upgrade guide, [매일한글] (Maeil Hangul)!

Today, we’re moving beyond K-dramas and daily slang to explore something deeper: the profound, almost magical, role language plays in Korean cultural rituals. Ever wondered why specific words are used during holidays or ceremonies? You’re about to find out!

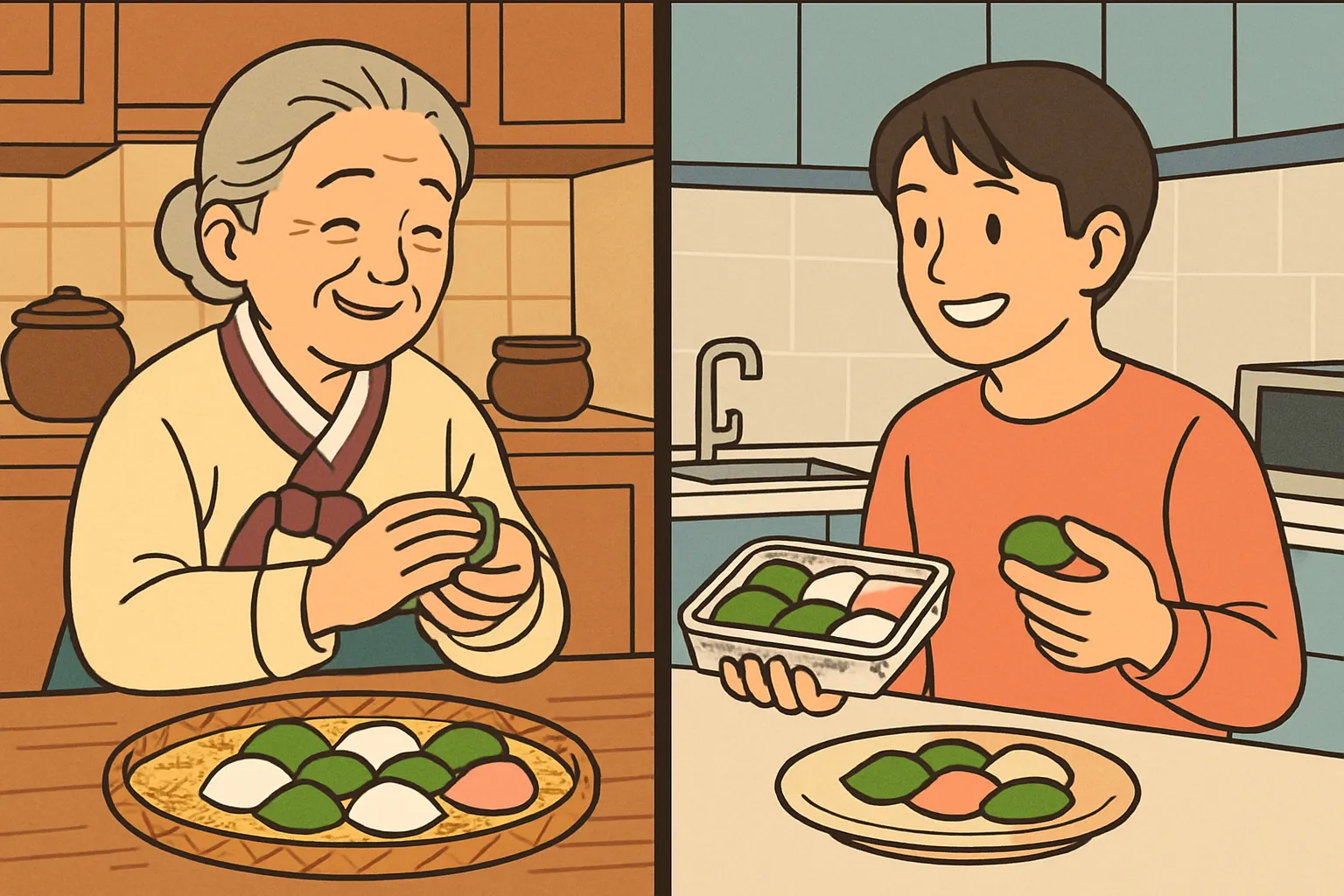

Lately in Korea, there’s a fascinating conversation happening. As family structures and lifestyles change, many are re-imagining traditional ceremonies like jesa (ancestral rites). They might order pre-made food or simplify the steps. But even in these modern versions, the specific, traditional language used remains incredibly important. It’s the key that connects the past to the present. Let’s dive into the linguistic anthropology of modern Korea!

Core Ritual Expressions

Here are some essential words that are more than just words—they are actions, concepts, and blessings all rolled into one.

1. 축문 (祝文) [Chungmun]

- English Meaning: Ritual Prayer; Written Address to the Spirits

- Detailed Explanation: A chungmun is the formal, written prayer read aloud during a jesa (ancestral memorial rite). Traditionally written in Hanja (Chinese characters) and following a strict format, it serves as a formal report to the ancestors. It states the date, who is conducting the rite, and expresses gratitude and reverence. It is a perfect example of how language formalizes and legitimizes a ritual act. In modern times, many families simplify the chungmun or even write it in contemporary Korean to make it more accessible, but the act of formally reading it remains a pivotal part of the ceremony.

- 💡 Pronunciation Tip: The characters are ‘축(chuk)’ and ‘문(mun)’. When spoken together, there isn’t a complex sound change, but pay attention to the unaspirated ‘ㅁ(m)’ sound. It’s a soft ‘m’, not a hard one. The full phrase 축문을 낭독하다 [Chungmuneul nangdokada] (to read the ritual prayer) contains 낭독 [nangdok]. Here, the final consonant ‘ㅇ(ng)’ in 낭 influences the ‘ㄷ(d)’ in 독, but the sound remains distinct. Focus on a clear separation: [nang-dok].

2. 음복 (飮福) [Eumbok]

- English Meaning: “Drinking/Receiving Blessings”

- Detailed Explanation: This is a crucial concept. Eumbok refers to the act of consuming the food and drink that were offered to the ancestors during the jesa. It is not simply “eating” (먹다). The act of eumbok is a performative utterance in itself; by eating the ritual food, participants symbolically internalize the blessings and goodwill of their ancestors, completing the communion between the spirit world and the living. It transforms a meal into the final, essential step of a sacred rite.

- 💡 Pronunciation Tip: The word is composed of ‘음(eum)’ and ‘복(bok)’. When spoken, it’s a straightforward [eumbok]. However, notice the Hanja: 飮 (to drink) and 福 (fortune). The pronunciation doesn’t reflect the complex meaning, which is why understanding the etymology is key for advanced learners.

3. 정성 (精誠) [Jeongseong]

- English Meaning: Sincere heart; heartfelt devotion; true sincerity

- Detailed Explanation: Jeongseong is a foundational cultural concept in Korea that is paramount in rituals. It refers to the immense care, sincerity, and effort put into an action. In the context of a ritual, preparing the food with jeongseong and performing the rites with jeongseong is often considered more important than the material value or quantity of the offerings. Linguistically, stating that something was “done with jeongseong” elevates the action from mundane to meaningful. It’s the invisible, yet most crucial, ingredient.

- 💡 Pronunciation Tip: The ‘ㅅ(s)’ at the end of 성 is followed by the particle ‘을(eul)’, it links to the next syllable. So, 정성을 [jeongseong-eul] is pronounced [정성을/jeongseongeul]. The key here is the tense consonant ‘ㅆ’ in the related verb 쏟다 (ssotda – to pour), as in 정성을 쏟다 [jeongseong-eul ssotda] (to pour out one’s sincerity). Practice the sharp, tense [ss] sound, which has no direct equivalent in English.

4. 고수레 [Gosure]

- English Meaning: An offering cry for the spirits.

- Detailed Explanation: This is a fascinating remnant of Korean folk beliefs and shamanism. Before eating or drinking outdoors (like on a hike or a picnic), one might take a small piece of food or pour a few drops of drink on the ground while saying “Gosure!” This is a ritualistic utterance, an offering to the local spirits and ghosts (gohon) to appease them and ensure a safe meal. It is a performative act that acknowledges the spiritual world. While less common among younger generations, it is still a well-known cultural practice.

- 💡 Pronunciation Tip: The romanization is ‘Gosure’, but the Korean ‘ㅓ(eo)’ vowel in ‘고(go)’ is often tricky. It’s not ‘go’ as in “go away.” It’s a more open sound, similar to the ‘o’ in ‘song’. The ‘ㄹ(r/l)’ sound in ‘레(re)’ is a light flap, like the ‘r’ in the Spanish word ‘caro’. Practice saying it quickly and lightly: [Go-su-re].

Example Dialogue

Here’s how these terms might appear in a conversation between two cousins, Minjun (A) and Sora (B), preparing for a simplified Chuseok (Korean Thanksgiving) ceremony.

A: 소라야, 이따가 읽을 축문인데, 내가 다들 이해하기 쉽게 현대어로 다시 써봤어.

(Sora, this is the chungmun we’ll read later. I rewrote it in modern Korean so everyone can understand.)

B: 와, 좋은 생각이다! 형식보다 정성이 중요한 거잖아. 끝나고 다 같이 음복하면서 조상님들의 복을 나누는 것도 잊지 말자.

(Wow, great idea! The jeongseong is more important than the formality, right? And let’s not forget to eumbok together afterwards and share the ancestors’ blessings.)

A: 물론이지. 이따가 할아버지가 밖에서 막걸리 한잔하시면서 “고수레!” 하고 외치셔도 놀라지 마.

(Of course. And don’t be surprised if Grandpa yells “Gosure!” later when he has a glass of makgeolli outside.)

B: 하하, 그런 건 변하면 안 되지. 그게 우리를 이어주는 거니까.

(Haha, things like that shouldn’t change. It’s what connects us.)

Culture Tip & Trend Analysis: The “Modern Jesa”

The dialogue above hints at a major cultural shift in Korea. Many younger Koreans feel that traditional rituals, especially jesa, are an immense burden, leading to what’s called jesa jeung-hugun (제사 증후군, “jesa syndrome”).

In response, a new trend of “modern jesa” is emerging. This includes:

* Meal Kits: Ordering pre-made, high-quality “제사 키트” (jesa kits) online.

* Location Change: Holding rites at modern memorial parks instead of the eldest son’s home.

* Simplification: Reducing the number of dishes or replacing the rite with a family meal or vacation.

In this evolution, language becomes a powerful anchor to tradition. Even if the food is from a kit and the chungmun is read from a tablet, using terms like 음복 (eumbok) and emphasizing the importance of 정성 (jeongseong) preserves the sacred meaning and spiritual core of the ceremony. The language acts as a bridge, ensuring that even a modernized ritual is seen as legitimate and respectful, connecting the family to its heritage.

Time to Practice!

Let’s wrap up! Today we learned that in Korean rituals, language isn’t just descriptive; it’s performative. It makes things happen, transforms objects, and connects people to a spiritual and historical legacy.

Your Turn:

- Consider the English phrase “I promise.” This is a ‘performative utterance’—saying it makes it so. How does the Korean verb 음복하다 (eumbok-hada) function similarly within the context of jesa? Explain in your own words.

Leave your answer in the comments below! Have you ever witnessed or participated in a Korean ritual? We’d love to hear about your experience